Events

Learn

Te Whakaminenga

He Whakapūtanga

Te Tiriti ō Waitangi

Ngā WAI TOHU

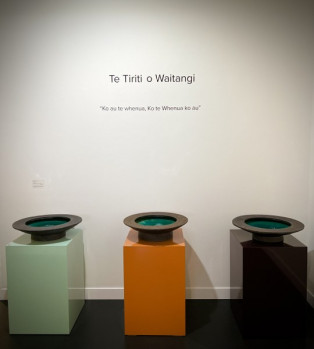

“Ko au te whenua, Ko te Whenua ko au”

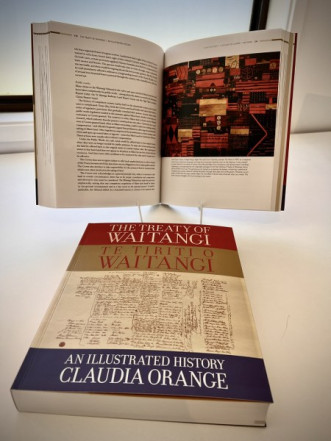

Ngā WAI Tohu (The Signatures) at Waiheke’s Community Gallery, Te Whare Taonga o Waiheke, is the seventh of the gallery’s annual exhibitions addressing Te Tiriti o Waitangi. Te Tiriti was signed by Ngāti Paoa rangatira from Waiheke, Hauraki Gulf and Waitematā at Karaka Bay in 1840.

The title, Ngā WAI Tohu, honours the signatories to that document and those who signed two previous documents leading up to Te Tiriti.

Te Whakaminenga o ngā Hapū o Niu Tireni, the original indigenous Māori preamble to the Declaration of Independence, began in Taranaki in 1820–25. It was formalised at Pouārua, Hauraki by the United Confederation of Chiefs in 1825-30, honed by Northern Rangatira into the final draft in 1830-35 and agreed to at a General Assembly of the Tribal Nations of New Zealand.

He Whakaputanga o te Rangatiratanga o Niu Tireni (The Declaration of Independence of the United Tribes of New Zealand), signed in 1835 at Waitangi, proclaimed the sovereign independence of New Zealand prior to the signing of Te Tiriti in 1840. It was a powerful assertion of Rangatiratanga, indigenous independence and authority, which 52 chiefs had signed by July 1839, and which was formally acknowledged by the Crown in 1836.

Te Tiriti o Waitangi signed on February 6 1840, encapsulates the final settlement where two nations, the indigenous Māori chiefs and representatives of the British Crown, signed their consent to the ratified terms and conditions.

Te Whakaminega identifies to the world who the United Assembly of Chiefs were in relation to He Whakaputanga - the Declaration of Independence, which is our Disclosure Document of Sovereignity. Te Tiriti o Waitangi covers the Co-Governance, Protection of Rights, our indigenous way of life and our Taonga.

Ngā WAI Tohu also honours the claimants who lodged Wai 262 with the Waitangi Tribunal in 1991 seeking to “restore rangatiratanga o te iwi Māori in respect of flora, fauna and all of our taonga”. This claim was the focus of 2023’s Te Tiriti exhibition.

“Everything has a whakapapa and a mauri (lifeforce),” states Lorna Rikihana (Ngāti Paoa, Ngāti Haua, Ngāti Koheriki, Ngāti Wairere) in the artists’ brief for the exhibition. She concludes her comments, “And this is no less true for Te Tiriti itself. These Wai Tohu signatures,” she says, “are our legacy of that commitment in the pursuit of the goals to build our nation in the belief of honesty, integrity and respect of this Tiriti.”

Kia Ū, kia Mataara; “Toitū te Tiriti”

Be strong, be vigilant; Honour the Treaty

Co-curated by Lorna Rikihana and Sylvia Nelson, Ngā WAI Tohu offers artists a platform to respond to Te Tiriti while promoting discussion and understanding around the significance of New Zealand’s founding document.

Contributing artists have responded to the whakataukī: Ko au te whenua, ko te whenua ko au (I am the land and the land is me) through exploration of their individual connections to Papatūānuku and the elements of fire, earth, air and water involved in their individual art practice.

All are well-established artists, exhibiting both nationally and internationally. Mike Crawford is Dunedin-based, Christine Thacker, Paora Toi Te Rangiauia, Penny Ericson and Denis O’Connor are all senior artists with studios on Waiheke, while Ida Edwards, Noelle Jakeman, Amorangi Hikuroa, Karuna Douglas, Todd Douglas and Dorothy Waetford are all trailblazing ‘second generation’ Māori ceramic artists of the the Ngā Kaihanga Uku Collective.

Acclaimed writer and performer of poems, Moana Te Aira Te Uri Karaka Te Waero Clarke (Ngāti Paoa, Uri Karaka) has written and performed a new poem written specifically for Ngā Wai Tohu. Referencing Te Tiriti o Waitangi and Mahuika, Goddess of Fire, it was a pertinent beginning to an exhibition of works with fire at its core, set in Tāmaki Makarau with its 53 volcanos, 18 of which have recently had their Māori names reinstated.

Mike Crawford’s (Ngāti Raukawa, Scottish, Pākehā) research into gourds and their traditional use as vessels for storing preserved birds has seen him combine those forms.The Kererū resides in the ngāhere, the Tākapu (Gannet) on the coast. Each has whakapapa and its own mana, yet their stories are intertwined - with points of connection and difference. The birds, echoing the form of Egyptian canopic jars, operate as sentries, keeping watch across whenua and moana. The title He Manu ki Uta, He Manu ki Tai (A Bird Inland, a Bird at Sea) is a tweak on the two kiwaha (idioms): 'he raru ki uta' meaning a smaller problem and 'he raru ki tai' meaning a difficult problem. In thinking about the issues we face, whether big or small, te taiao and kōrero tuku iho can help us navigate through. Ko te mana whakahaere Māori mō ngā mea Māori. Māori control of Māori things.”

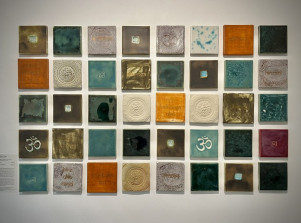

The wall tiles of Indian New Zealander Karuna Douglas testify to her passion and skill for glaze chemistry carrying the intense colours of her ancestral homeland and her crystalline glazes referencing Aotearoa’s dynamic and volatile landscapes.

“My work ,” she says, “exists in the layers just below and just above the clay. It’s only microns thick but in that space, I can create a universe. As ngā tauiwi, I was honoured to be invited to exhibit in this exhibition. This honour led me further in my personal journey of discovery and understanding of my own indigeneity, as well as my responsibilities as an indigenous woman standing in a space that is not mine by right, a space to hold, in a land a world away from my ancestral homelands.

My research has taken me from Te Whiti o Rongomai and Parihaka to Mahatma Gandhi and The Salt March in India, following the threads that birthed the independence of a nation … and then back from India to Aotearoa following ancient migration routes. In this work, I bring it all together, who and where I come from, alongside who I’ve become, for as surely as we shape the land, the land shapes us.”

Todd Douglas (Ngāpuhi, Ngāti Manu, Te Mahurehure), Pākehā, Scottish, Welsh) is known for the broad range of ceramic techniques and surface treatments used in his pieces. “My work,” he says, “stems from a love of uku (clay). When I work with it, everything about it, from its tactile nature to its transformation in the kiln, grounds me. Each stage of the making is a transformation that you nurture and guide. You can't force uku. You have to allow it to change and become. Just as I transform the clay, it transforms me.”

“These vessels are an attempt to process the experience that was the climate event, Cyclone Gabrielle, 12 months ago. Evacuated and homeless immediately after the cyclone, I’ve been drawn to weather and landscape, in particular the similarities and connections between the Earth’s ocean currents vs atmospheric rivers, and isobaric pressure systems vs topographical contours.

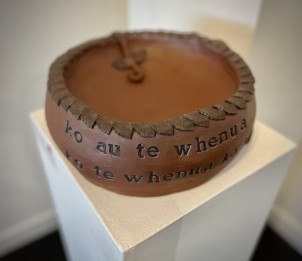

In her earth-coloured bowl which carries the inscribed whakataukī of this exhibition, Ida Edwards (Ngāpuhi) references whakapapa, and our connections to each other and to the land. Leaves encircle the rim of the bowl while tendrils emphasise new growth - one entering the bowl in the form of a koru. She frequently references Mahuika in her work. “it is fire that captures the essence of the ceramic process,” she has said. “It is one of the most powerful elements used to create and immortalise uku into utilitarian forms or creations that give voice to our whakapapa, to the beauty that surrounds us, and to the inspiration of te reo.”

The 18 glazed discs of Penny Ericson’s wall work The Magic of the Earth (Te Mauri o Te Whenua) make clear her fascination with the land, their widely varying surfaces formed from the very clay on which she lives. “With these works I’ve explored our natural clays, sands and minerals, the ceramic process capturing them in ways that mimic nature’s natural processes.” Some will have gone through five firings to achieve the desired effects, her skills formed over years of experiments with clays, slips and glazes. The three large rimmed stone-coloured vessels with the depth created by their iridescent turquoise glazes also speak of her connection with the moana. “I’ve lived on the coast all my life,” she says, “and what I’m doing is just the reflection of 70 years of walking on rocks and playing in rock pools as a child, living right beside the sea. It’s there - inside you.“

Amorangi Hikuroa (Ngāpuhi, Ngāti Maniapoto, Ngāti Toro, Te Popoto) draws from from his Ngāpuhi whakapapa and their rich history of whakairo design.”I see it as a privilege to be part of the whakapapa of Uku – the ancient history connecting us to our Pacific tupuna. Weaving narrative and the elements into his work he honours stories old and new, fire, water, weather, and the great oceans that link all lands.”

“2017 was the 30th birthday of our movement, Ngā Kaihanga Uku / Māori Clay Workers Collective. Clay is now and forever a media used by Māori. How long does an art form have to be practised before it is called a 'traditional practice’? We have avenues where clay is now utilised within our culture, made relevant by our mentors and founders of Ngā Kaihanga Uku… I pay homage to my ancestors, the greatest of navigators, and the first clay workers of the pacific. They left a map, a guide for us to follow, so we will always know where we’re from, where we are and where we’re going. We are all clay, the body of the mother.”

In 2023’s exhibition, Noelle Jakeman (Ngāti Hine, Ngā Puhi, Ngāti Maniapoto) exhibited a group of small clay anime and comic book-inspired figures as The Protectors. Her use of uku emphasising the connection Maori have to the land. “I also try to highlight some of those issues we face as tangata whenua,” she has said. Papa Palette references Papatūānuku through the forms of wahine wrapped in korowai (mantles of prestige and honour) and the natural earth ochres (kokowai) which colour them. Hung in a tāniko pattern which repeats the triangular form of the tiles themselves, they symbolise the solid and sturdy maunga and puke formations of the whenua.

Working in an English pottery and viewing collections of European medieval pottery whilst in the UK have been a powerful influence on Christine Thacker’s work, as attested to by the form of her terracotta jug - an iconic shape in European pottery. As a canvas, it enables her to paint around its form, but a jug, she says, can also provide a sense of comfort. Painting is a key component of her clay work. “Every potter working in earthenware is probably at heart a painter,” she has said. “The bonus with painting on pottery is we are able to seal our painted imagery in an enlivening coating of glass so it can shine like a stone under water.”

The jug, depicting a volcano and seascapes, is entitled 'And we came to this land of good times'. The wall tiles, two of them carrying views of land approached from the sea, also “take their titles from the lyrics of Land of Plenty, written and performed by Pauly Fuemana and the Otara Millionaires Club. It is an important immigrant song for all tauiwi,” she says. “In her book The Human Condition, Hannah Arendt speaks to “the possibility of keeping promises.” Promises, Thacker says, should be kept.

“I like how working with uku involves getting to know the corporeal nature of clay,” Dorothy Waetford (Ngāti Wai, Ngāti Hine, Ngāpuhi Nui Tono) has said, “how it responds to air, water and heat.” She has spoken also of being intrigued by growth, contradiction, movement and evolution - factors relevant to language and the layering of meaning in works such as WAI which she sees as a wellspring of language. Through its scale and colouring the word itself is given physical clarity and stature, inviting contemplation not only of the element it names but its place in cultural narratives along with the power and complications of language itself. It references both Wai 262, the claim commonly known as the indigenous flora and fauna and cultural and intellectual property claim filed in 1991 and still in progress, and Te Tiriti Article 2 itself. Delicately worked patterning draws attention to other ways in which narratives and histories are carried and transmitted.

Works by two of Waiheke’s best known artists kaitiaki the exhibition.

Sculptor Paora Toi Te Rangiuaia (Ngāti Porou) with a wakahuia and two feathers carved from obsidian - the volcanic glass formed by rapidly cooling lava. Worn to symbolise leadership and mana, the feathers, and their further connection with quills and writing, reiterate the importance of the signatures to He Whakaputanga and Te Tiriti o Waitangi and honour the tipuna (ancestors) who signed them.

The frosted globe of Equator, by sculptor Dennis O’Connor is blank except for an equatorial band inscribed with the names of the artist’s two grandsons who whakapapa to both Tainui and Ireland. Inscribed on its base: ”The Irish harp is not constructed but carved out of a single tree like a canoe” speaks of the more natural approach of indigenous cultures. Narratives of migrations and the binding together of people through intersecting histories and whakapapa are inherent in this work.

Lorna Rikihana (Ngāti Paoa, Ngāti Haua, Ngāti Koheriki, Ngāti Wairere),

Lorna is a Māori Woman visual artist with a Masters of Fine Arts. She has governance and operational skill sets that allow her to traverse engagement with Government and Council at Board level and work in the field of building capability of Marae beneficiaries in Kawa and tikanga. Her passion is Toi Tukuiho either advocating for, or pushing the boundaries within exhibitions in order to provoke more discussion around Toi Māori.

Sylvia Nelson

Co-curator Sylvia Nelson, together with the late George Kahi, initiated the annual Te Tiriti o Wai-tangi exhibitions in 2018. Sylvia is an artist whose career has spanned commercial interior design, exhibition design, project management, and artist and gallery management. She has been involved with the Te Tiriti exhibitions since their inception.

Text: Sandra Chesterman

Subscribe to our newsletter and receive a monthly update on exhibitions, events and programmes at the Gallery.

Subscribe To Our NewsletterSign up to our newsletter and receive a monthly update on what‘s happening at Waiheke Community Art Gallery.